Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture (SUWA)

Reflecting on the Journey of Supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals since 2015

What is at stake

About two-thirds of the global population live under conditions of severe water scarcity for at least one month in a year (Mekonnen and Hoekstra 2016). This is only going to get worse thanks to climate change. Out of our freshwater consumption, 70–80 per cent goes to the agricultural sector (Lautze et al. 2014). However, we often forget to ask ourselves if we really need drinking quality water for agriculture.

At the same time, we produce over 330 km3 of wastewater on a global scale each year (Mateo-Sagasta et al. 2015), yet over 80 per cent of it does not receive any treatment and flows back into the natural ecosystem (UN-Water 2014), polluting the limited supply of freshwater we have for human consumption.

Given these critical issues that we currently face as a global community, it is key to realise that the solutions lie within these challenges. If all types of wastewater are to be treated by all means, then the treated wastewater can be used for agricultural irrigation, which presents a sustainable way to alleviate water scarcity. How did we miss something so simple and so attractive?

A fundamental part of the issue is related to our ignorance – to look at wastewater as a resource. While many regions of the world are facing water scarcity, and at a time where circular economy or the circularity of resources is being recognised as the way to go, the rate of water recycling stays at a very low level on a global scale (Sato et al. 2013). This translates to millions of gallons of resources that could have otherwise been put to good use.

Turning this challenge into an opportunity helps us unleash the untapped resource and give it its true worth. The recycling option is also a blessing for public health and the environment, as it means treating wastewater before it can be used again. However, managing wastewater is a costly challenge for many countries. One-third of the global population is still lacking access to improved sanitation (UNESCO 2017). Poor management of wastewater is undoubtedly causing damage to the environment and public health alike.

Target 6.3 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) requires us, by 2030, to “improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally” (emphasis added).

The safe use of wastewater can, therefore, be understood as the use of treated wastewater. If done safely and properly, water recycling not only solves some of the issues in water scarcity and brings us closer to achieving Target 6.3 but also adds value to our efforts in addressing issues in health and agriculture. In fact, it goes beyond: from being a source of energy for households to providing nutrients in agriculture, the benefits of the use of wastewater is vast.

Photo by Keagan Henman on Unsplash

Photo by Keagan Henman on Unsplash

Photo by Romanenkova on shutterstock

Photo by Romanenkova on shutterstock

Photo by PhenomArtlover on iStockphoto

Photo by PhenomArtlover on iStockphoto

“The benefits of water reuse are enormous. Wastewater is so much more than dirty water – in agriculture, it can increase yields, cut the need for fertilisers, and improve soil quality; and if collected and treated properly, it could provide drinking water. In addition, the by-product of sewage treatment – sludge – can be used to produce energy. Some treatment plants even use it for renewable energy purposes.”

Excerpt from “Wastewater for a Better Future, Not Waste Water”

“The use of wastewater demonstrates how the sustainable management of one resource in a nexus can benefit the other resources in the same nexus. Irrigation with wastewater not only addresses the water demand issues in water-stressed areas but also helps us “recycle” the nutrients in it.”

Excerpt from “Keynote Speech on the “Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture in the Light of Nexus Thinking” at Soil-Waste-Water 2018 (SWW18)”

“An integrated approach is required. Integrating wastewater into the production of food and non-food biomass is part of a nexus solution to the problem of soil degeneration. One practical manifestation of such is the project “SUWA: Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture”.

Excerpt from “Understanding the Resource Linkages in the Water-Energy-Climate Nexus”

Looking at treated wastewater as a sustainable way to supplement irrigation water needs, this idea also supports SDG 12 (Sustainable consumption and production), particularly in agricultural production. More than 20 million hectares of land were being irrigated with wastewater by 2010 (FAO 2010). However, a more recent study revealed that this number could be much higher if the indirect use of it, such as the use of wastewater diluted in fresh water, especially in urban settings, is included in the estimations (Thebo et al. 2017). Mainly, wastewater is used for irrigating non-leafy vegetables and water lawns or gardens. Global changes – population growth, rapid urbanisation, and climate change among others – add pressure on freshwater resources, driving millions of farmers to make use of wastewater.

While the increasing use of wastewater in agriculture is a positive sign for the circularity of resources, unfortunately, much of it is not based on any scientific criteria ensuring its safe use. Due to a lack of awareness or poverty, there is continued use of blackwater – wastewater that contains human waste –instead of greywater – wastewater generated without faecal contamination. Various forms of materials found in wastewater such as antibiotic-resistant bacteria may pose a major risk to the health of its end user. The benefits of water reuse may come at the cost of public health, if not managed properly.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Photo by Jamie Street on Unsplash

Photo by Jamie Street on Unsplash

“Superbugs – or antibiotic-resistant bacteria – develop in wastewater and could end up in our food. The effects of these micropollutants in the water environment, however, are complex and are still not fully understood. In order to ensure that the water that goes into irrigating our food crops is of decent quality, we need to tackle the topic of antimicrobial resistance.”

Excerpt from “Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance for Food Safety”

“After we take an antibiotic to treat bacterial infections, the resistant bacteria in our bodies are excreted, and eventually reach a wastewater treatment plant. Studying wastewater represents a critical part of understanding the spread of antibiotic resistance, especially if treated wastewater is used as reclaimed water. With treated wastewater increasingly being used in agriculture to achieve sustainable water management in arid regions, resistant bacteria may find its way into our food as well.”

Excerpt from “Superbugs Evolve in Wastewater, and Could End Up in Our Food”

Progress towards Target 6.3 of the Sustainable Development Goals will also help achieve the SDGs on health and wellbeing (SDG 3), safe water and sanitation (SDG 6), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), life below water (SDG 14), and life on land (SDG 15), among others.

There are as many opportunities for wastewater use as there are benefits. Given how nature’s cycles of water, nutrients, and carbon are all interconnected, exploiting these linkages enables us to unlock multiple functions within the whole system. Spanning across the nexus of water, soil, and waste, wastewater use is an excellent example that naturally explains the importance of the integrated management of these three resources, as embodied in nexus thinking.

When we talk about “protecting and restoring water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers, and lakes”(sic) as demanded by Target 6.6 of the SDGs, it is fundamental that we also look to the big picture and study the synergies and trade-offs of different processes to better inform the way we handle the individual resources.

The SUWA Initiative

UNU-FLORES’s Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture (SUWA) initiative aims to raise the awareness of and push to implement minimum standards for water reuse for agricultural purposes.

While it is important to recognise the benefits of using wastewater, it cannot be denied that there are also risks involved. As reiterated by the United Nations World Water Development Report 2017, there is a critical need to improve the management of wastewater for a sustainable future (WWAP 2017).

In 2011 the UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development (UNW-DPC) in Bonn hosted by UNU, together with several other UN-Water members, partners, and programmes joined efforts to launch a capacity development initiative addressing the safe use of wastewater in agriculture (SUWA). Between 2011 and 2013, these activities brought together 150 participants – mostly ministerial representatives – from 70 UN Member States In 2015, when UNW-DPC ceased operations in fulfilment of its mandate, UNU-FLORES breathed new life into SUWA, advancing its original capacity development objective while putting science at the forefront.

“Despite remarkable progress during the ‘Water for Life” Decade — such as halving the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water five years ahead of the Millennium Development Goal target date — water remains one of the major challenges of our time. Capacity development is a crucial tool to address current and future challenges.”

Excerpt from “Event Celebrates Achievements of UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development”

Photo by David Ress on Unsplash

Photo by David Ress on Unsplash

In line with Target 17.16 that requires that we “enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, to support the achievement of the sustainable development goals in all countries, in particular developing countries”, the subsequent phase of SUWA was designed to to support UN Member States in developing their national capacities in focus areas, promoting a safer and more productive use of wastewater. Developing countries and countries in transition remain to be the focus.

UNU-FLORES’s SUWA journey began with a workshop in Lima, Peru in February 2016. UNU-FLORES organised the workshop “Good Practice Examples and Future Research Needs” with the support of Promoción del Desarrollo Sostenible, United Nations Environment Programme, and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. The workshop aimed to facilitate knowledge exchange and to identify future research needs.

“In order to address the technical, institutional, and policy challenges of safe water reuse, developing countries and countries in transition need clear institutional arrangements and more skilled human resources, with a sound understanding of the opportunities and potential risks of wastewater use. Sharing information between countries/regions on “good practice examples of safe water reuse in agriculture” is the first objective… The second objective of the workshop is to identify the knowledge gaps in the SUWA-related activities where there is a need for further research.”

Excerpt from “Good Practice Examples and Future Research Needs”

Target 17.6 of the SDGs requires us to “enhance North-South, South-South and triangular regional and international cooperation on and access to science, technology and innovation and enhance knowledge sharing on mutually agreed terms, including through improved coordination among existing mechanisms, in particular at the United Nations level, and through a global technology facilitation mechanism”.

The Lima workshop of 2016 brought together experts, researchers, and ministerial representatives from 16 different countries. The participants had the opportunity to learn about seventeen case studies from South America, Asia, and Africa in which wastewater is being used for agricultural purposes. The discussions at the workshop arrived at one important conclusion: the policy dimension, particularly related to the implementation of wastewater use in agriculture, is a significant challenge.

The outcome of the workshop enabled stakeholders to set the research agenda for the current phase of SUWA. This is fundamental before it was possible to “enhance international support for implementing effective and targeted capacity-building in developing countries to support national plans to implement all the sustainable development goals”, as outlined by Target 17.9 of the SDGs.

“In particular, participants struggled with the questions: How much regulation is needed to control the use of wastewater in agriculture? Or, where should the line be drawn between no regulations and strict regulations? In addition, achieving a better understanding of the health and environmental safety concerns was of considerable interest to most participants.”

Excerpt from “Policy Concerns Dominate Discussion on Reusing Wastewater in Agriculture”

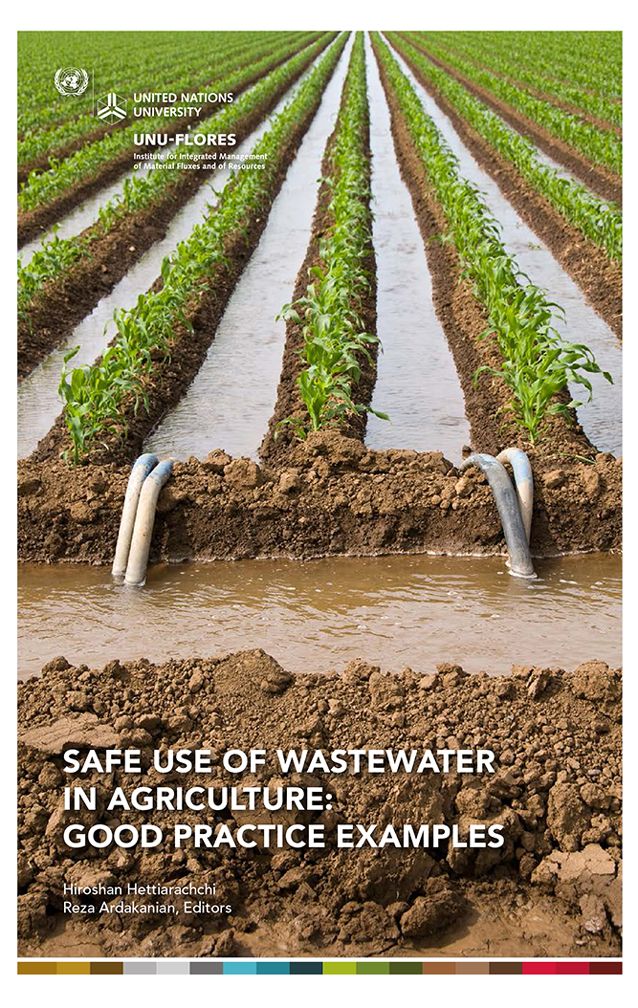

As identified by the earlier objectives of the initiative and has resonated at the workshop, a sound understanding of the opportunities and potential risks of wastewater use is necessary, particularly to support policy and implementation. A direct result of the Lima workshop, the publication Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples (2016) – a compilation of existing cases across different continents – provides a good starting point.

Launched in conjunction with the 2016 World Water Week in Stockholm, the edited volume covers cases from Brazil to South Africa and Nepal and features 17 case studies exemplifying the practice of wastewater use in agriculture across the globe.

Target 13.3 of the SDGs urges us to “improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning”.

The book addresses three dimensions of SUWA amid our current environmental challenges: technological advances, health and environmental aspects, and policy and implementation issues. Made available in four languages – English, Spanish, Farsi, and Arabic – it is a useful resource for governments keen on learning from existing practices. Not only is the editors’ aim to enhance North-South but also South-South knowledge sharing.

“Iran is not a rich country in water resources. However, it could be stated that the main challenge in Iran’s water sector is not water shortage, but the poor management of resources… This book published by UNU-FLORES, as a pioneering international institute, is an example of sharing experiences of different countries at the global level. It is hoped that Iran can overcome the challenges of the water crisis through extensive assessment of the current situation and applying practical approaches and strategies with collaboration of all stakeholders in the water sector.”

Reza Ardakanian, Minister of Energy, Islamic Republic of Iran, in Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples in Farsi

“A contribution publicising the importance of water and sensitising Arab communities to the need to conserve and optimise their use. ALECSO thanks UNU-FLORES for the right to translate and republish the book (in Arabic), allowing us to place the knowledge in the hands of researchers in the Arab countries.”

H. E. Dr Saud bin Hilal Al-Harbi, Director-General of the Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organisation (ALECSO), in Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples in Arabic

On Building Capacity

In order to bolster all-around sustainable development, we need a holistic approach towards it. A combination of capacity development on various levels ensures that we not only address sustainability issues at the individual but also at the systemic level.

UNU-FLORES’s SUWA initiative took on capacity development on two main levels: national (including grassroots) and individual. Together, it allows for a more sustainable outcome in the imparting of knowledge and skills as well as achieving the safe use of wastewater in agriculture.

The Lima workshop that took place in 2016 provided insight on hotspot areas where SUWA needed to be tackled. Researchers and practitioners from around the world shared their experiences during this workshop and helped to identify the future research needs. Many of them offered to continue their support in the years to come, and as seen in the following, this idea did materialise. The workshop launched the opportunity for the SUWA initiative to take on capacity development on the state – to some extent, grassroots – level by working with Member States to advance the good practices of SUWA in their respective countries.

Aligned with Target 6.a calling for the “[expansion of] international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including… water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling and reuse technologies”, UNU-FLORES identified opportunities to build capacity in SUWA in four developing countries across three continents: Iran, Mexico, Tunisia, and Colombia.

It is hoped that by inspiring stakeholders in Iran to adopt SUWA, it brings us a step closer towards achieving Target 2.3: “By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers… including through… productive resources and inputs, knowledge… and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment.”

Photo by Vicente Velasco Velasco/ITVO

Photo by Vicente Velasco Velasco/ITVO

The Mexico workshop was attended by the representatives of all stakeholder groups, including several local farmers. The participation of the local community, especially the farmers, was very important not only because it was an opportunity for them to receive information first-hand, in the spirit of local empowerment, but also an opportunity for the non-local experts to learn from them. In the same vein, the local political leadership also contributed to several sessions. Moisés Ramírez (Major of Tepeji del Rio) and María Luisa Pérez Perusquia (President of the Congress, The State of Hidalgo), were notable among them.

With the field visit facilitated by the local stakeholders in Tunisia, efforts were in place to “support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management” (Target 6.b).

As in the Iranian case, introducing the concept of SUWA and having it successfully accepted by the Colombian authorities brings us closer towards achieving Target 2.3. Despite having water availability six times the global average, parts of Colombia have only a tenth of the average levels in terms of access to water supply. In a country where the water demand is increasing in tandem with the growing agricultural sector, SUWA is a key alternative to increase water availability for agriculture in Colombia.

Photo by NWWEC

Photo by NWWEC

“While policies and regulations covering the use of wastewater may be traced back to the Natural Resources Code in 1974, direct regulation is covered only by more recent developments since 2014. When it comes to implementation, only two cases of wastewater use in agriculture have been documented in Colombia.

Based on the state of affairs, Jiménez highlighted how current regulation ignores both the potential of municipal treated wastewater as a resource of agriculture and the farmers as end users. This restrictive view sees wastewater only as a water resource and neglects its potential in providing nutrients. As a result, it mostly promotes the use of industrial wastewater in agroindustrial crops, when in fact Colombia is a country of smallholder farms.”

Excerpt from “Scarcity in the Midst of Abundance: Colombia’s Water Situation and How SUWA Can Address It”

Through the international workshops conducted in developing countries that could benefit most from SUWA, the initiative helped “promote the development, transfer, dissemination and diffusion of environmentally sound technologies to developing countries on favourable terms… as mutually agreed” (Target 17.7).

In particular, the book Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: From Concept to Implementation (2018) puts together the wisdom gathered from the discussions at the Tehran workshop in one publication. It addresses potential challenges in the process of SUWA implementation and discusses the technical, institutional, and policy opportunities by applying first-hand information on the Middle East and North African region, and Europe.

“Complementing the book Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture: Good Practice Examples (2016), the 2018 publication describes the status of wastewater use on a broader and global level. Authors discuss the subject of wastewater management, focusing on the practical aspect of the issue and analyse potential repercussions. In so doing, the new book bridges the gap between theory and practice by providing guidelines on the implementation of SUWA through a novel approach. It is the first book to consider interdependencies within the Water-Soil-Waste nexus and their integrated management.”

Excerpt from “Taking the Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture from Concept to Implementation”

To reinforce the capacity building done at the national level, the SUWA initiative at UNU-FLORES also took on efforts to enhance individual capacity. From internships to research visits, such endeavours are intended to empower especially the youth to become champions of SUWA in their respective fields and home countries.

Arjun Avasthy (India), Intern (2016)

“Water is a limited resource – optimising its use is essential. Use of wastewater in agriculture could be vital to fight against the water resource scarcity and in addressing risks posed by unsustainable urbanisation and agricultural and industrial intensification. However, the road ahead is still long. At UNU-FLORES, I gained a variety of experiences and skills and having the opportunity to learn from seasoned professionals gave me someone to look up to and a goal to work towards. It instilled high work ethic in me and an ambition to go above and beyond what was required.”

Diana Carolina Riano Guzman (Colombia), Intern (2016/17)

“At UNU-FLORES, I had the chance to work with an amazing team of experts (my supervisors) and colleagues (other interns and PhD students) that enrich my experience. I had the chance to pique my scientific curiosity about resource management and different approaches to this theme.”

Read “It Takes Lots of Curiosity, and a Little Confidence” in full

Ana Lilia Velasco Cruz (Mexico), Visiting Scholar (2018)

“SUWA is one important piece of the puzzle to counter global threats such as water scarcity and natural resources conservation. SUWA could increase the value of wastewater via nutrient recycling in agriculture and thus buffer the increasing worldwide loss of soil fertility. I hope we will finally place emphasis on the ‘S’ without removing the nutrients in SUWA and bring safety to the forefront – through treatments that are environmentally friendly and financially achievable – to minimise the impact of pollution on natural resources via wastewater. Subsequently, implementation according to the local context of different countries will be needed. SUWA is key to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6. The evident benefits that SUWA could provide to developing countries easily correlate to the increasing interest in and application of wastewater treatment in such countries. UNU-FLORES gave me not only the knowledge on how other countries deal with SUWA but also provided me access to a network of academic experts that deal with the same topic.”

Read “Of Quinoa and Wastewater: An Interview with Ana Lilia Velasco Cruz” in full

Natalia Jiménez Contento (Colombia), Visiting Scholar (2018/19)

“To improve people’s quality of life, we need a solid, inclusive, and holistic environmental policy. SUWA as a concept is attractive for two reasons: it is practical for farmers and by ensuring its safe use, SUWA helps unlock the potential of nutrients found in wastewater. My goal is to give applicable recommendations to the Colombian government for incorporating SUWA as an adaptation strategy to climate change. And I hope this will result in the development of a policy and regulations that can be readily implemented and enforced in a cost-effective way, maximising health and environmental benefits.”

Read “From Lima to Dresden: Natalia ‘Gets Dirty’ for Food Security” and “’Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture Means to Achieve Sustainable Development’: An Interview with Natalia Jiménez” in full

Policy Relevance

For science and advocacy to have as wide and deep an impact, they need to inform policy. Influence towards and at best a change in policy would mean embedding the values of, for example, SUWA in a system that would continue to ensure their relevance and application on a wide scale.

Following the capacity development workshop in Colombia, UNU-FLORES played a vital convening role to bring both scientists and policymakers on one stage. The International Dialogue on “Working at the Science-Policy Interface” that took place in June 2019 in Dresden, Germany illustrated SUWA as a case example of how science and policy actors have worked together on research and policy formulation. A scientist and a ministerial representative shared their experiences and lessons learned through the initiative. The discussions shed light on how science can shape policy and conversely, how policy can feed into science.

As Target 13.2 outlines, it is imperative to “integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning” and in the case of Colombia, the capacity development workshop in Bogota had resulted in stakeholders agreeing on the idea of developing a pilot project for SUWA. Its goal would be to generate information that would serve as technical support shaping the policy and regulation related to the use of treated wastewater in agriculture. The authorities had also invited UNU-FLORES to be part of the pilot project.

“When it comes to governing the commons – resources that belong to a whole community – the intersections of science and policy are inevitable. Scientists, in particular, are urged to take the lead by doing three things: identify the needs of policy, engage with the right stakeholders, and maintain connections for sustainable impact.

As part of a team drafting a regulation on wastewater use, Natalia Jiménez saw the lack of implementation and wondered why that was the case. This prompted her to join UNU-FLORES as a Visiting Scholar and Alexander von Humboldt Climate Fellow to get her questions answered herself.

Supporting this line of argument, a representative from the same Ministry Carlos Andres Palacio admitted that if more knowledge were to be made available to governments, they could make better policies. Speaking on the panel, he raised how critical it is to have data that is made usable for policymakers. He recalled the value of having access to the expertise and network UNU-FLORES offers on the Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture (SUWA). He appreciated how new opportunities arose by inviting international experts to Colombia.”

Excerpt from “For a Meaningful Science-Policy Interface, Scientists Have to Do These Three Things”

By bringing together different policy actors, there is also a higher chance that different authorities would work collaboratively to “substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity” (Target 6.4). The Bogota workshop brought together over 40 participants including representatives from the Ministries of Environment, Housing, and Agriculture, as well as 26 representatives from regional environmental authorities to exchange knowledge and share possible solutions for improving the regulatory framework for promoting SUWA in Colombia. Bringing together the various stakeholders in one room to align their work around water reuse – resulting in the initiative for a collaborative pilot study – was an unprecedented achievement.

SUWA projects and case studies around the globe (Image: Atiqah Fairuz Salleh/UNU-FLORES)

SUWA projects and case studies around the globe (Image: Atiqah Fairuz Salleh/UNU-FLORES)

Beyond Colombia, the activities throughout the SUWA initiative have reached and benefitted a wide number of stakeholders worldwide. The infographic provides a summary of the geographic distribution and number of local partners involved and participants attended of the SUWA workshops and the regions covered by the case studies in the book publications resulting from the initiative.

Tackling SUWA at multiple levels simultaneously – national, grassroots, individual – help reinforce the lessons from it and altogether advance our efforts to “ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality” (Target 2.4).

References

Ardakanian, R., Liebe, J., and Bernhardt, L.M. 2015. Reporting Achievements 2007-2015, UNW-DPC, Bonn, Germany.

FAO. 2010. "The wealth of waste: The economics of wastewater use in agriculture", Water Report # 35. Rome, Italy: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Lautze, J., Stander, E., Drechsel, P., Da Silva, A. K. and Keraita, B. 2014. “Global Experiences in Water Reuse.” Resource Recovery and Reuse Series 4. Colombo: International Water Management Institute (IWMI)/CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems. Available: www.iwmi.cgiar.org/Publications/wle/rrr/ resource_recovery_and_reuse-series_4.pdf.

Mateo-Sagasta, J.; Raschid-Sally, L.; Thebo, A. 2015. "Global wastewater and sludge production, treatment and use." In: Wastewater: Economic asset in an urbanizing world, ed., Drechsel, P. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Mekonnen, M. M., and Hoekstra, A. Y.. 2016. “Four billion people facing severe water scarcity.” Science Advances 2:2. Available: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500323.

Sato T., Qadir, M., Yamamotoe, S., Endoe, T., and Zahooraet, A. 2013. “Global, regional, and country level need for data on wastewater generation, treatment, and use.” Agricultural Water Management 130:1–13.

Thebo, A.L., Drechsel, P., Lambin, E.F., and Nelson, K.L. 2017. "A global, spatially-explicit assessment of irrigated croplands influenced by urban wastewater flows." Environmental Research Letters 12:7. IOP Publishing Ltd.

WWAP. 2017. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2017: Wastewater, The Untapped Resource. Paris, France: United Nations World Water Assessment Programme (WWAP), UNESCO.

Photo/video credits (in order of appearance, if not already included): SimonSkafar/iStockphoto, Subham Das, UNU-FLORES, jarun011/iStockphoto, Reza Baradaran Esfahani, Olfa Mahjoub, Cristian Rivera Machado